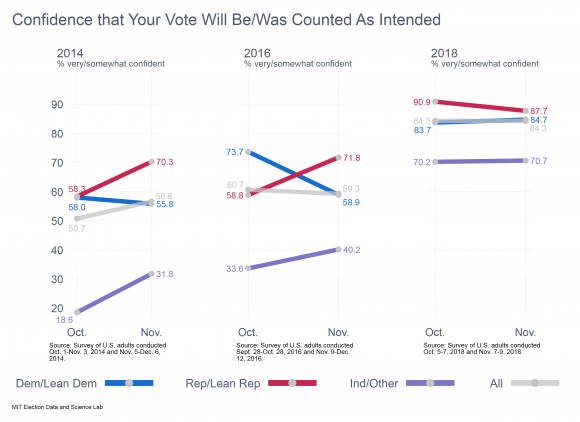

For the past two decades, Americans have consistently exhibited a “winner’s effect” in judging whether votes were counted fairly in elections. The 2018 election broke that pattern.

In particular, prior to 2018, it was common for voters who identified with the prevailing party in a federal election to acquire much greater confidence post-election that votes were counted as intended. Conversely, members of the vanquished party became much less confident.

Not in 2018.

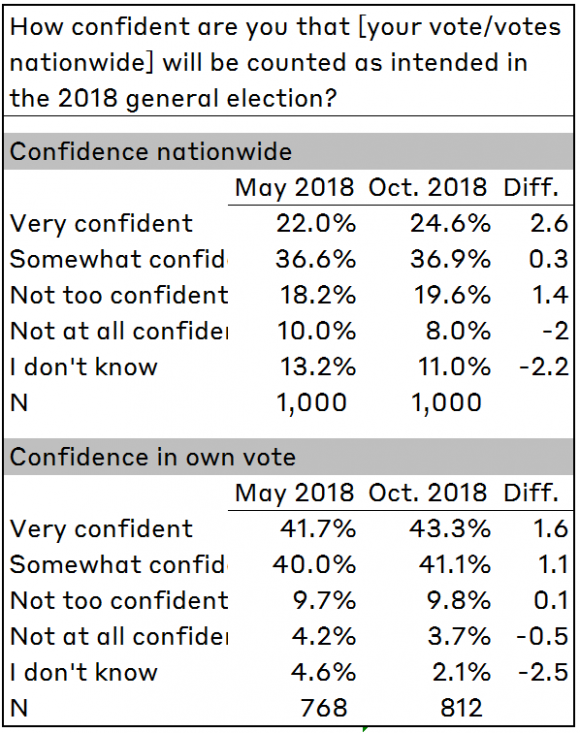

In a nationwide survey of adults I conducted in the days immediately after the 2018 federal election, 84% of voters stated they were either “very” or “somewhat” confident that their vote was counted as they intended. (Throughout this post, I will refer to these respondents as “confident.”) This is virtually identical to the response they gave a month before the election. In contrast with patterns from past elections, the results of the election had no effect on overall levels of confident, and essentially no effect on differences between the parties.

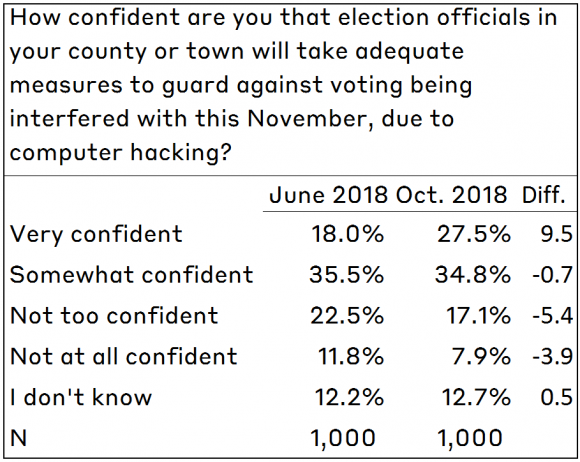

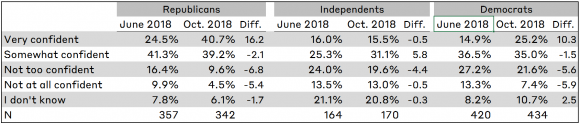

The data in this post were taken from two surveys I conducted before the election (during May 14–16 and October 5–7) and one after (on November 7–9). In each case, the surveys interviewed 1,000 adults as a part of the YouGov Omnibus survey. The research was supported by a grant from NEO Philanthropy, which bears no responsibility for the results or analysis. I will contrast the results I found in 2018 with similar research I performed in the 2014 and 2016 federal elections, plus a peer-reviewed article I published in 2015 with Mike Sances, which examined the history of voter confidence from 2000 to 2012.

Voter confidence in the 2018 election

The focus of this post is on two questions that form the core of research on attitudes about public confidence in election administration. Asked after the election, the questions are:

- How confident are you that your vote was counted as you intended?

- How confident are you that votes nationwide were counted as intended?

The questions can also be asked before the election, in which case they are altered slightly to reflect the fact they are being asked prospectively. (E.g., “How confident are you that your vote will be counted as you intend?”) There are variations on this question across researchers, but they all tend to produce very similar response patterns.

Voters in 2018 were like voters in past years in one important respect: they expressed greater confidence that their own vote was (or would be) counted as intended, compared to opinions about vote-counting nationwide. For instance, after the election, 84% expressed confidence that their own vote was counted as intended, compared to 61% of respondents who said the same about votes nationwide.

Voters in 2018 were like voters in past years in one important respect: they expressed greater confidence that their own vote was (or would be) counted as intended, compared to opinions about vote-counting nationwide. For instance, after the election, 84% expressed confidence that their own vote was counted as intended, compared to 61% of respondents who said the same about votes nationwide.

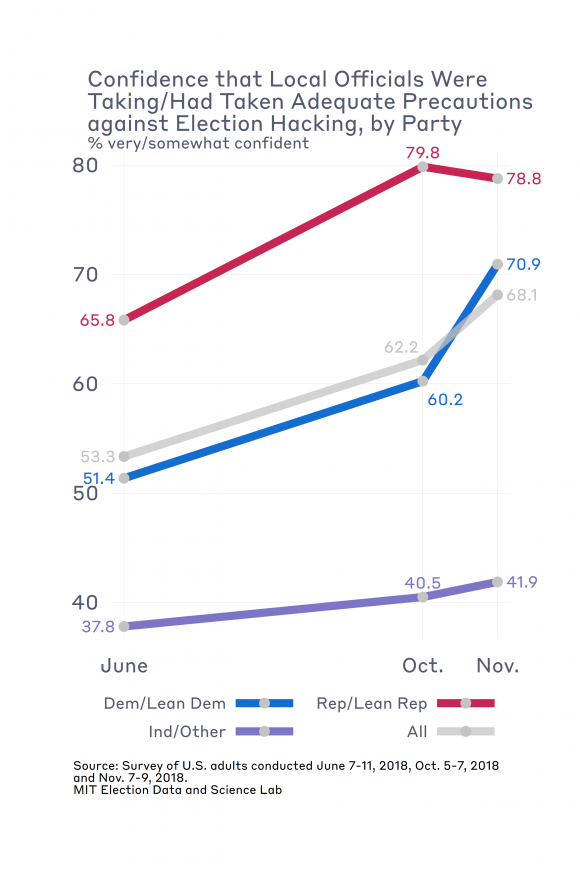

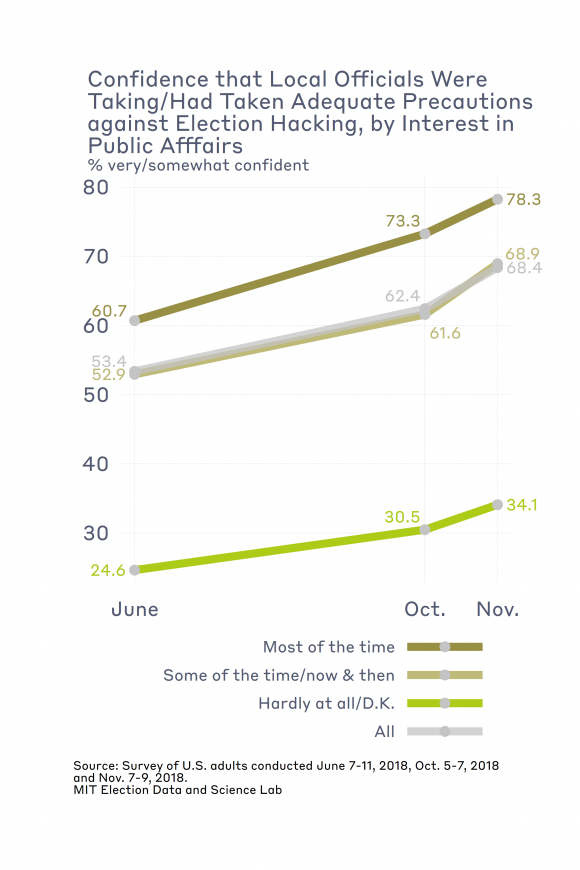

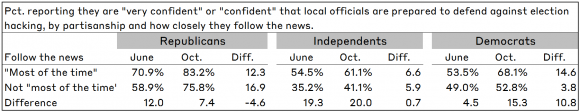

Ever since questions about voter confidence have been asked, starting with the 2000 election, answers have tended to divide along partisan lines, depending on who was in power and which party was perceived to have won the most recent election. A partisan divide also appeared in 2018, both before and after the election. For both questions, Republicans expressed greater confidence than Democrats during the pre-election period. After the election, the two parties converged when the question was about their own vote, but the divide remained when the question was about vote-counting nationwide.

Before exploring these patterns in more detail, it is notable that voter confidence grew between May and October among partisan identifiers, but it dropped among respondents who identified with neither of the major parties. The election itself seems to have deflected these patterns only a bit. Yet, the movements in opinions after the election are so small that any changes in early November may have been due to random noise.

Comparison with past year

The patterns in voter confidence that emerged in 2018 are remarkable when we place them beside results from past years. In an article that Michael Sances and I published in Electoral Studies in 2015, we found that starting in 2000, and running through 2012, there was a tendency for voter confidence to improve after elections. We don’t see that in 2018. We also found that there was a tendency for the “winning” party’s adherents to be especially confident in the quality of the vote count post-election. We also don’t see that in 2018.

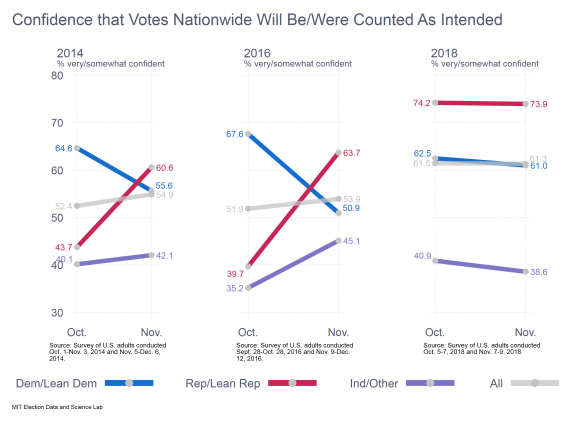

To help illustrate how unusual the 2018 patterns are, even compared to the recent past, I went back to research I conducted in 2014 and 2016, using data from my module in the the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES). In both years, I asked a sample of adults the voter-confidence questions I have been discussing here, before and after the election. In each election, all the patterns related to partisanship were consistent to what Sances and I found when we explored earlier years. The patterns in 2014 and 2016 were also different from what we see in 2018.

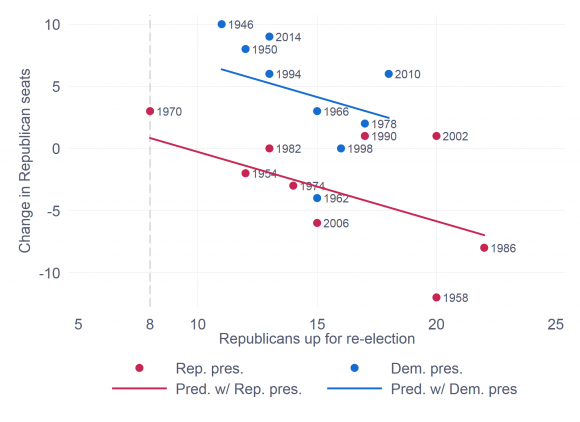

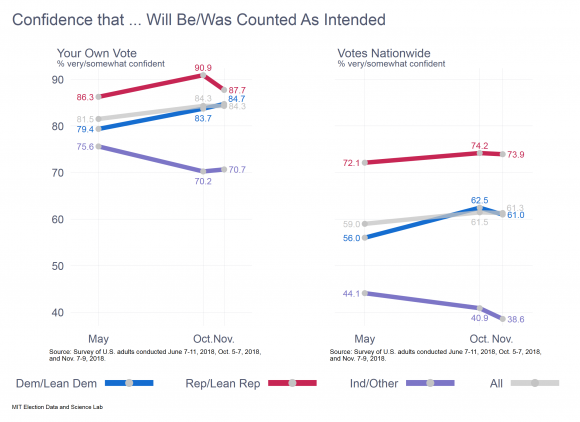

The accompanying graphs show how the question pertaining to confidence in one’s own vote was answered in 2014, 2016, and 2018. The pre-/post-election change in confidence in 2018 stands in stark contrast with what we saw in 2014 and 2016. In 2014, for instance, Democrats and Republicans were equally confident one month before the election.* Just a month later, the results at the polls revealed a set of solid Republican victories in federal and state elections nationwide. Good electoral news for Republicans was followed by a 14-point increase in Republican confidence and a slight decrease in confidence among Democrats.

In 2016, the even-more-dramatic electoral results produced an even greater shift in partisan confidence. One month before the election, Democrats were more confident by a margin of 15 points. Right after the election, Democrats were less confident, by 13 points.

Turning our attention to the question about how the respondent felt about the vote-count nationwide, we see some interesting differences across the years, but the same stark contrast between 2018, on the one hand, the 2014 and 2016, on the other.

Turning our attention to the question about how the respondent felt about the vote-count nationwide, we see some interesting differences across the years, but the same stark contrast between 2018, on the one hand, the 2014 and 2016, on the other.

In shifting our attention away from local vote counting toward attitudes about elections nationwide, it is notable that in both 2014 and 2016, Democrats went into the election with a much more sanguine view about the state of election administration than Republicans did. And, in each year, the partisan shifts in attitudes after the election were substantial. Not so with 2018, where Republicans started out much more confident than Democrats before the election, and stayed that way afterwards.

Parting thoughts

These results just skim the surface of what we have yet to learn about voter confidence in the 2018 election. As data from the large academic surveys come available in the new year, we’ll be able to explore the contours of voter confidence with much greater nuance than I’ve been able to do here.

I must underscore that the post-election results from 2018 are based on a survey that was in the field the two days after the election. Responses, therefore, are largely unaffected by election-counting controversies that unfolded in the days and weeks ahead, in Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina. Nor do they reflect responses to the “blue shift” in the returns, as California and other west-coast states completed the count in the following weeks.

For the past two years, close observers of election administration have wondered whether the current political climate is corrosive to trust in our electoral process. The results I’ve reported here are inconsistent with the view that Americans are less trusting of their elections — or at least the administration of elections. Overall, Americans expressed more confidence that their votes were counted as intended in 2018 than in either 2014 or 2016. Although there is a significant partisan divide between Republicans and Democrats in levels of confidence, both at a local and national level, it must be underscored that Democrats in 2018 were still more confident than they were in 2016, or even 2014 for that matter.

What is unusual about 2018 is the fact that Democrats did not become more confident after the election, despite the fact that the party retook the House and held its own in the Senate. In past years, a blue wave in the election returns would have resulted in Democrats feeling much better about the electoral process than they apparently did in 2018. ** This might be a sign that Democrats have begun to internalize a critique of the electoral process that focuses on efforts to raise barriers to participation in some states. Alas, we can’t probe questions like this with the data we have.

As questions of election administration become more politicized, it is natural to wonder whether this politicization is eroding confidence in the process among Americans. The preliminary evidence here is that it has not. However, the preliminary evidence is also that Americans may be changing how they think about whether they are confident in how elections are run. If voters are beginning to think about confidence in the system in terms of the long-term political allegiances, rather than in terms of short-term winners and losers, then the world of voter confidence will have changed.

Notes

*The analysis here focuses on the difference between the October and November numbers because they are the most comparable data points. Unfortunately, I did not have public opinion soundings from late spring/early summer, like I did this year.

**Of course, it might also be the case that the 2018 post-election survey was held too close to the election for the fact that this was a blue-wave year to sink in on Democrats.