One of the big stories to come out of Tuesday’s hearing of the Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity (PACEI) is about the divisions that have begun to show among commissioners over how alarmed we should be about stories that people with out-of-state driver’s licenses vote, or what we should conclude from evidence that a very small fraction of voters in 2016 may have voted twice.

The story I am referring to was the comment made by one of the commissioners, Maine Secretary of State Matthew Dunlap, who was quoted as saying, “Maybe I’m being too cynical, but they [i.e., most of his fellow commissioners] are looking at voter fraud as being if legislatures are making it too easy for people who don’t own property in a town to register there.”

Secretary Dunlap is on to something.

Back in 2013, as I was reading through Alex Keyssar’s masterful The Right to Vote with a graduate student, we hit upon the idea of asking voters whether they thought a range of reforms that had been enacted by legislatures or imposed by courts had improved democracy. So, in the 2013 Cooperative Congressional Election Study, we threw in the following question:

Lawmakers and courts often get involved in laws that decide who can vote, and the methods people can use to vote. We would like to ask you questions about laws and court decisions that have been made over the years. Some of these laws and court decisions have affected voting throughout the entire United States. Some have affected only voters in a particular city or state.

Please give us your opinion about whether you believe these court decisions or laws have improved the quality of elections in the United States or diminished the quality of elections.

The court decisions and laws we asked about were these:

- Giving 18-year-olds the right to vote.

- Abolishing the requirement that people pay a poll tax in order to vote.

- Giving women the right to vote.

- Allowing non-citizens to vote in local elections.

- Requiring all representative districts to have equal populations.

- Requiring that people who have difficulty speaking English be given voting assistance in a language they feel more comfortable with.

- Allowing people who do not own property to vote.

- Prohibiting racial discrimination in voting.

- Allowing students who are away at college to decide whether they vote back home, or where they are in school.

- Allowing soldiers who are stationed away from home to decide whether they vote back home, or where they are stationed.

- Limiting the residency requirement in order to vote to only a couple of weeks.

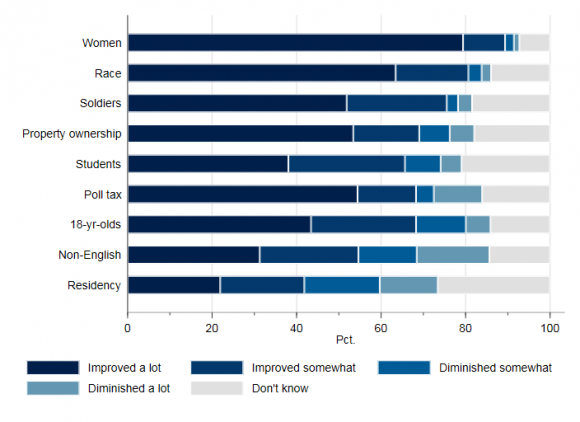

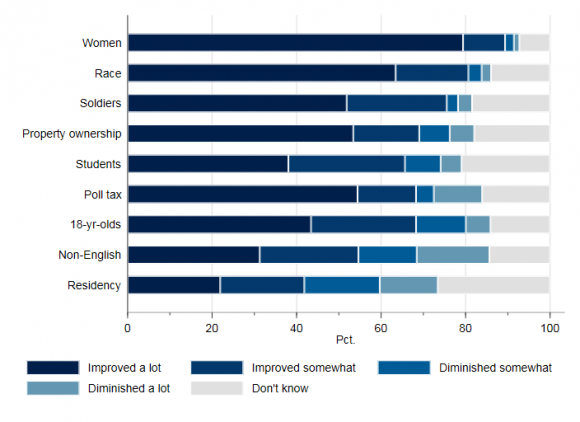

The graph below summarizes the answers to these questions.

(I have left off the equal population item, because it’s not directly related to voting access, and the non-citizen voting item, because so few localities have actually allowed this. Equal-population districts were not especially popular among the respondents, and non-citizen voting in local elections was very unpopular.)

Among these ballot-access reforms, the least popular was “limiting the residency requirement in order to vote to only a couple of weeks.” A bare majority (53%) thought that eliminating property requirements had improved elections a lot; fewer thought that allowing students to decide whether they voted back home or where they were in school had improved elections.

Overall, respondents to the survey expressed majority support to some degree for all of these reforms, except for shortening the residency requirement. Still, significant minorities thought some of these items had diminished the quality of elections, and non-trivial fractions couldn’t express an opinion about most of the items.

The overall pattern of responses does not reveal an anti-democratic impulse among the citizenry. Rather, the overall pattern shows a diversity of opinions that Americans have about the expansion of voting rights over the past century. Most are on board, but many have qualms.

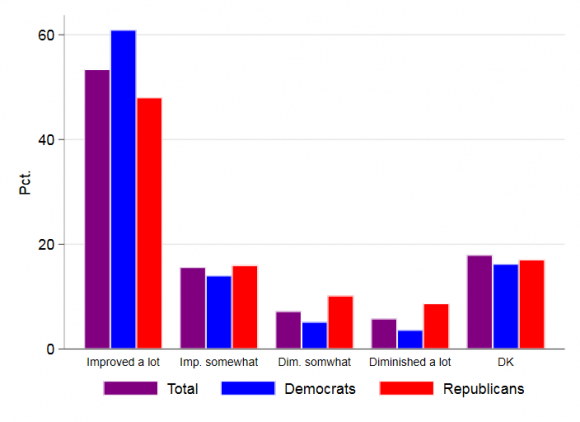

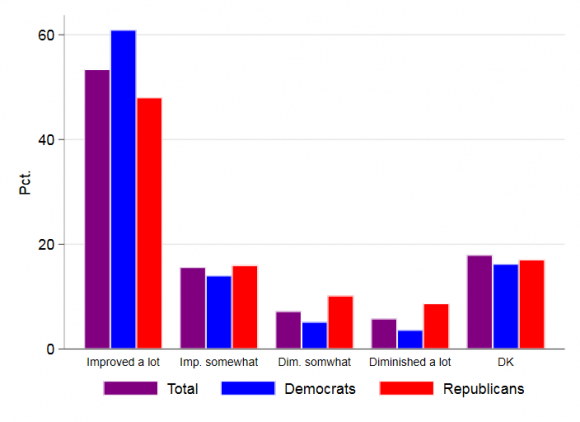

Not surprisingly, there is a partisan dimension to these opinions, but the divide is not as great as it is on other hot-button issues in American politics. Take the property ownership question, for instance. The bar graph below shows how Democratic and Republican respondents answered this question. While Democrats were more likely to say that removing property qualifications had improved elections “a lot,” and Republicans were more likely to say that removing property qualifications had diminished elections, the partisan differences were relatively small.

Bigger differences emerge when we drill down and examine partisans who have differing opinions about voter fraud. Both parties had contingents who worry a lot about voter fraud and those who don’t, although the contingent of worriers was larger among Republicans. In the same survey, we asked respondents to place themselves on a continuum, anchored by the phrases “I am worried about voting fraud” and “I am not worried about voting fraud.” Among Republicans, 65% placed themselves on the “worried” end of the spectrum, compared to 29% of Democrats.

Among the worried Republicans, 25% believed removing property requirements diminished elections, compared to 7% of non-worried Republicans. Among the worried Democrats, 7% believed eliminating property requirements diminished elections, compared to 8% of non-worried Democrats.

Similar analyses emerge when we look at the other items. The greatest skepticism about ballot-access expansion is generally focused on “worried Republicans.”

To return to Secretary Dunlap’s point, the commentary he provides about his colleagues has application to the mass public. Not everyone is comfortable with the expansion of ballot access over the past century. People who are especially worried about fraud are especially uncomfortable. Republicans are less comfortable than Democrats, but there are internal divisions, especially among Republicans.

Before I conclude, I must add the obvious caveat. The survey I have been discussing was done four years ago. The partisan divide on these questions has no doubt expanded in the ensuring years, though other survey evidence I have seen suggests that the divide on election administration questions hasn’t expanded as much as some would think. (If someone out there would like to pay for my repeating the survey now, I’d be happy to talk to you.)

The survey results I have been discussing allow us to appreciate even more the significance of the e-mail message released on Tuesday by the Campaign Law Center, written by Hans von Spakovsky, from before he was appointed to the PACEI, criticizing the possible appointment of a bipartisan commission that would include “mainstream Republican officials” and Democrats. As that e-mail suggests, and the survey evidence bears out, there is some diversity of opinion among Republicans about the wisdom of franchise-expanding reforms and about whether voter fraud is something to worry about. The e-mail is empirically incorrect in inferring that no Democrats worry about voter fraud and that Democrats are uniform in their opinions about franchise-expansion.

Many of my friends and colleagues have expressed alarm about the appointment and work of the PACEI. One of the reasons I have not expressed the same degree of alarm, even when I have criticized the commission’s charge, is that the attitudes that appear to motivate the most influential members of the commission reside in a sizeable portion of the American public. It is a fair question about whether the diversity of attitudes on the commission reflect the diversity of attitudes in the American public. Secretary Dunlap is right to raise the question.