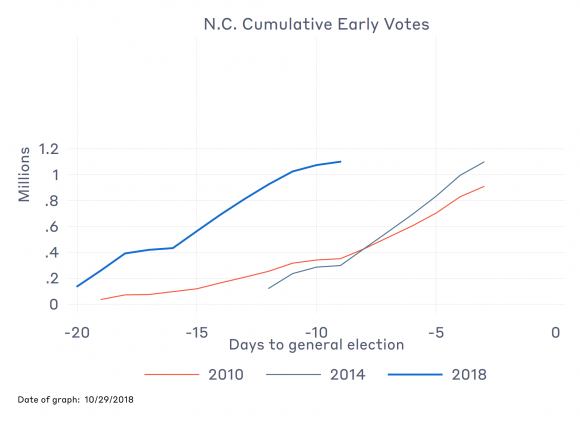

The number of people voting early, in person, in North Carolina — what most of the country calls “early voting,” but what North Carolina calls “one-stop absentee voting” — has exploded in 2018. (For this post, I will use the more common term “early voting” to refer to North Carolina’s one-stop process.) As of last weekend, over 1.1 million Tar Heels had cast an early vote, which is essentially the total number of people who cast early votes in all of 2014, and roughly three times the number of early votes cast at comparable times in 2010 and 2014.

So what?

Two things make this interesting. First, in most states, North Carolina included, early voting has been a presidential-year phenomenon, with early voting rates falling back in midterm years. For instance, in 2012 56% of all North Carolina ballots were cast early; in 2014, that fell to 37%. In 2016, 60% of ballots were cast early. That would lead us to believe that something like 40% would be cast early in 2018 under normal circumstances. Let’s say that a total of 3.5 million North Carolinians will vote this year, which is a 20% increase over 2014, and in any other year would be an outrageous prediction. Forty percent of 3.5 million is 1.4 million early votes. We’ve nearly achieved that number, and we’re more than a week away from Election Day.

The second reason the surge in early voting is interesting is that North Carolina is not on the national radar this year. Its statewide offices are elected in presidential years, and neither U.S. Senate seat is up this cycle. Conventional wisdom has held that up-ticks in convenience voting — early and absentee voting — are typically driven by the campaigns, especially the national campaigns. The early voting surge in North Carolina is driven entirely by what’s happening in North Carolina, not by the mobilization efforts of the national campaigns. This is interesting.

To return to the data, the accompanying graph shows the cumulative number of early voters at comparable points in the pre-election periods of the three most recent midterm elections. (As always, click on the graph to enlarginate it.) The cumulative number of early votes for each year are plotted against a comparable “countdown to election day.” The three lines all start at different places along the x-axis, reflecting how the General Assembly has altered the early voting period over the past five years — reducing it by a week for 2014 (later struck down by the 4th Circuit) and then adding a day for 2018. As of yesterday, the preliminary count is over three times greater than at a comparable time in 2010 or 2014, and has already surpassed the number of early votes in 2014.

To return to the data, the accompanying graph shows the cumulative number of early voters at comparable points in the pre-election periods of the three most recent midterm elections. (As always, click on the graph to enlarginate it.) The cumulative number of early votes for each year are plotted against a comparable “countdown to election day.” The three lines all start at different places along the x-axis, reflecting how the General Assembly has altered the early voting period over the past five years — reducing it by a week for 2014 (later struck down by the 4th Circuit) and then adding a day for 2018. As of yesterday, the preliminary count is over three times greater than at a comparable time in 2010 or 2014, and has already surpassed the number of early votes in 2014.

What about party and race?

The total number of early voters is of interest to election geeks, both those interested in election administration and those interested in campaign mobilization. What about the politics of the numbers we see thus far?

Trillions of electrons are currently being spilled, trying to divine next week’s election outcomes based on the early vote totals. In North Carolina, at least, and probably elsewhere, that’s a fool’s mission. At best, the early vote numbers, broken down by party, are only weakly predictive of the final election results.

Nonetheless, part of the discussion about early- and absentee-voting numbers revolves around the types of voters who gravitate toward these modes. With that more minimalist perspective, what do the North Carolina numbers tell us?

Party

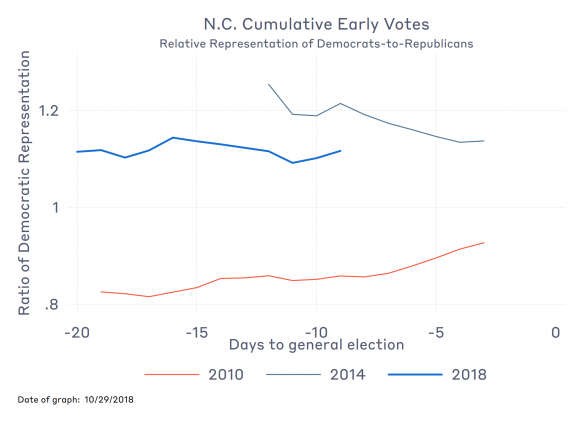

Let’s start with party. Are Republicans or Democrats more likely to avail themselves of early voting this year? Thus far, Democrats are more likely than Republican to use early voting, relatively speaking. However, compared to 2014, the disproportionately greater use of early voting by Democrats has declined. Thus, the surge in early voting in North Carolina is being driven more by the surge of Republicans than the surge of Democrats.

Here are some details.

As of yesterday, approximately 473,000 Democrats and 333,000 Republicans had voted early, which puts the Democrat-to-Republican ratio at 1.42:1 among early voters. This party ratio in the use of early voting needs to be compared to the Democrat-to-Republican ratio among registered voters, which is currently 1.27:1. Because 1.42 is greater than 1.27, we can say that Democrats are disproportionately using early voting. But, hold that thought; we’ll come back to it..

The accompanying chart shows how the ratio of Democratic-to-Republican early voters has played out in 2018, and in comparison with 2010 and 2014. The blue line in the graph essentially reproduces the calculation I performed in the previous paragraph for each day of early voting this year. It takes the Democrat-to-Republican ratio of early voters and divides by the Democrat-to-Republican ratio of registrants. Numbers greater than one indicate that early voting is being used disproportionately by Democrats; numbers less than one indicate early voting being used disproportionately by Republicans.

The accompanying chart shows how the ratio of Democratic-to-Republican early voters has played out in 2018, and in comparison with 2010 and 2014. The blue line in the graph essentially reproduces the calculation I performed in the previous paragraph for each day of early voting this year. It takes the Democrat-to-Republican ratio of early voters and divides by the Democrat-to-Republican ratio of registrants. Numbers greater than one indicate that early voting is being used disproportionately by Democrats; numbers less than one indicate early voting being used disproportionately by Republicans.

Note that this “ratio of ratios” measure has been quite different in 2010, 2014, and 2018. In 2010, early voting was used disproportionately by Republicans, although there was a significant surge of Democrats toward the end that brought its use into something closer to parity. In 2014, early voting was heavily favored by Democrats, especially at the beginning of the early voting period, with Republicans disproportionately coming in at the end to even things out a bit.

In 2018, the disproportionate use of early voting by Democrats has held steady for the past week. While Democrats are more likely to vote early in 2018 than Republicans, they are less so than in 2014. What this means, interestingly enough, is that although Democrats are more likely than Republicans to vote early in 2018 (at least thus far), the surge in early voting compared to 2014 is being drive disproportionately by a flood of new Republican early voters.

Race

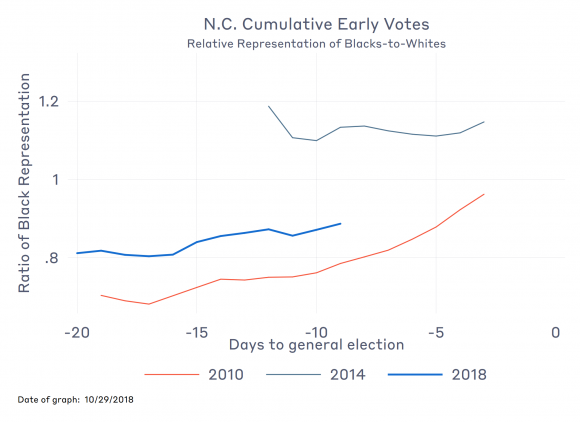

What about race? Thus far, it appears that African Americans have taken advantage of early voting at a lower rate than whites. This patterns is in stark contrast with 2014, when there are a significant surge toward early voting among African Americans, and similar to the patterns of 2010. Note that in 2010, and somewhat in 2014, there was an uptick in African American early voting participation as the early-voting period drew to a close. Thus, it may end up being that African Americans use early voting at rates comparable to that of whites in 2018, but it would be a shock to see the numbers begin rivaling those of 2014.

What about race? Thus far, it appears that African Americans have taken advantage of early voting at a lower rate than whites. This patterns is in stark contrast with 2014, when there are a significant surge toward early voting among African Americans, and similar to the patterns of 2010. Note that in 2010, and somewhat in 2014, there was an uptick in African American early voting participation as the early-voting period drew to a close. Thus, it may end up being that African Americans use early voting at rates comparable to that of whites in 2018, but it would be a shock to see the numbers begin rivaling those of 2014.

Conclusion

For the remainder of the early voting period, I plan to update the three graphs that are reported in this post. It will be interesting to see what these numbers go. Because early voting only accelerates as Election Day approaches, it is safe to assume that early voting this year will be of historical proportions by the end of the week. If the early voting rates match the 2016 rates, Election Day will be pretty quiet in the Tar Heel State, even as voting has changed significantly.