By Charles Stewart III, MIT

The most promising solution to instill physical distancing in elections during the current COVID-19 crisis is increasing the availability of vote-by-mail options. Another suggested strategy has been increased early voting. The idea behind both is to “dedensify” polling places. While moving people to voting by mail will certainly do this, it’s unclear that more early voting will.

Whether early voting is part of the solution depends on whether early voting locations are less densely populated than Election Day polling places. From my initial look at the data, they may not be—although a lot more work needs to be done to know for sure.

For starters, I looked at the wonderful data available from the North Carolina State Board of Elections’ ftp site. From the data there, I could find out how many people voted in 2016 at every early voting site in the state, and the day when they voted. I was able to match that information with other data on the site that reported the hours when these early voting sites were open. From that, I could calculate the average number of early voters in each site on each day.

In addition, I was also able to use the voter history file to calculate the number of people who voted in-person on Election Day at each precinct.

The accompanying figure illustrates the results. (Click on this and the other graphs to enbiggen.) Throughout the early voting period in 2016, the average number of voters in each polling place was in the 60-to-75 range. This contrasts with Election Day, when the average was 41.

The accompanying figure illustrates the results. (Click on this and the other graphs to enbiggen.) Throughout the early voting period in 2016, the average number of voters in each polling place was in the 60-to-75 range. This contrasts with Election Day, when the average was 41.

Thus, simply shifting Election Day voters to early voting, at least in North Carolina, is not an obvious strategy. In fact, in a state like North Carolina, the move to early voting would seem to benefit early voters even more than Election Day voters.

I must quickly add some caveats before moving on. First, North Carolina may not be representative. In 2016, 61 percent of voters cast ballots early, through what they call “One-Stop Absentee Voting;” 35 percent of votes were cast on Election Day, with the remaining 4 percent being cast by mail. Thus, the early voting sites may already be congested, which is unlikely to be the case in most states. Still, in 2016, early voting was the dominant mode in seven or eight states, North Carolina included. The analysis here may be the most relevant to these.

Second, this analysis assumes nothing else changes, other than shifting people from Election Day to early voting. For instance, it assumes no more early voting sites are created. Obviously, if more early voting sites were created and voters used them, density in these sites could drop.

In addition, I haven’t compared the actual rooms and buildings that house early voting sites and precincts. This is clearly one example of how particular facts are important. If the alternative is between a cramped church basement on Election Day or a large community center multi-purpose room for early voting, the multi-purpose room can probably handle an equal volume of voters more safely than the basement. The list of early voting sites in North Carolina includes all sorts of locations, most of which seem pretty similar to locations that are used for Election Day voting, as well.

Finally, this analysis hasn’t taken a look at the variability of voter density during particular times of the day. This, of course, is critical, for implementing safe physical distancing practices. We know from the research I have helped the Bipartisan Policy Center conduct and the academic research I have been a part of that there’s a crunch of voters on Election Day when the polls open. Referring back to the North Carolina graph, it wouldn’t surprise me to find out that the average polling place in North Carolina handled 80 voters per hour in the first hour of Election Day voting, before falling to an average of 30-35 the rest of the day.

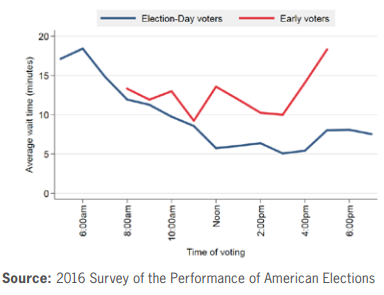

L ess observational research has been done of early voting sites. The survey research I have done suggests that arrival rates at early voting sites are spread more evenly across the day than on Election Day. The accompanying graph, which is taken from the 2016 report on wait times published by the BPC, shows average wait times at various times of the day, taking the nation as a whole. The good news is that there is not a beginning-of-the-day rush with early voting, over all. The bad news is that if there is congestion, it lasts all day long.

ess observational research has been done of early voting sites. The survey research I have done suggests that arrival rates at early voting sites are spread more evenly across the day than on Election Day. The accompanying graph, which is taken from the 2016 report on wait times published by the BPC, shows average wait times at various times of the day, taking the nation as a whole. The good news is that there is not a beginning-of-the-day rush with early voting, over all. The bad news is that if there is congestion, it lasts all day long.

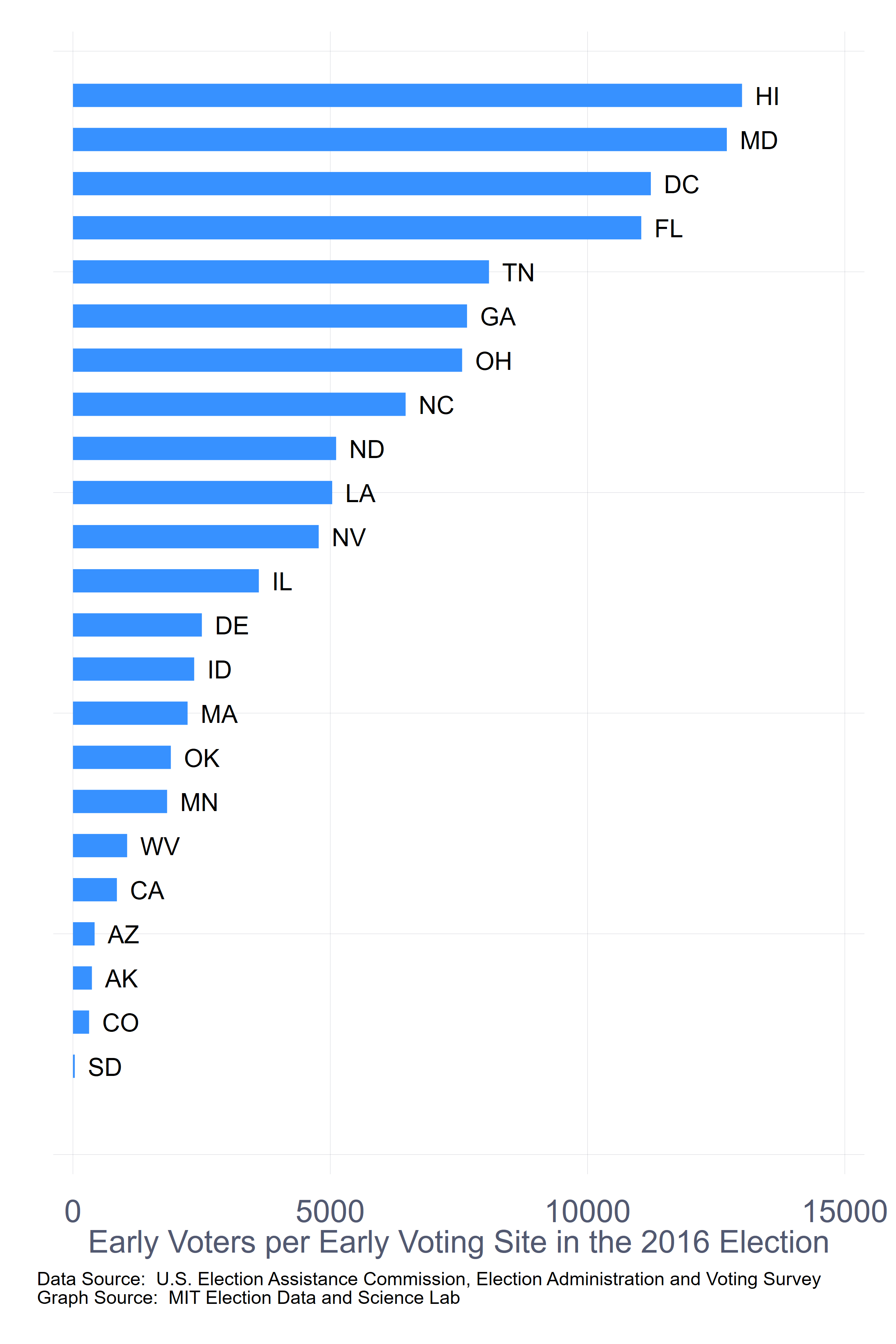

I end with one last figure, which shows the average number of voters who went through each early voting site among 23 states in 2016. The data are from the EAC’s Election Administration and Voting Survey. The states displayed are those that reported sufficient data to calculate meaningful statistics. (This means, for instance, that Texas, a state with a lot of early voting is excluded, because a lot of Texas counties did not report how many people voted early.)

I end with one last figure, which shows the average number of voters who went through each early voting site among 23 states in 2016. The data are from the EAC’s Election Administration and Voting Survey. The states displayed are those that reported sufficient data to calculate meaningful statistics. (This means, for instance, that Texas, a state with a lot of early voting is excluded, because a lot of Texas counties did not report how many people voted early.)

As with the North Carolina analysis, this is a rough first cut at getting a sense about where the most congested early voting sites might be. It’s rough, most obviously, because it doesn’t take into account how many days of early voting there are in the states, nor how many hours the individual sites were open. And, of course, it does not consider the variability in early vote center locations.

Also, some of the states with a highest early-voter-to-early-voting-site ratios are those without a lot of early voting, measured by the percentage of voters who use it. This looks to be true, for instance of Hawaii , Maryland, and D.C.

Nonetheless, as a first cut, it shows that the strategy of shifting more people to early voting in Minnesota or Massachusetts may be potentially more promising than doing so in Maryland or Washington, DC.

Analysis like this is no substitute for the detailed analysis that states and localities will be undertaking in the coming weeks, as they consider whether expanding early voting is right for them—and if it is right, how to do it.

It should serve as a cautionary note for the public and policymakers, however, as they clamor for “obvious” solutions to the problem of voting in the age of COVID-19. Nothing is obvious in this business. It’s all about the details. That’s why coming up with solutions that protect the 2020 election while protecting our health will take so much effort.