Commentary about the 2018 election often focused on two categories of worries that politicians, voters, and the punditocracy had about its administration — hacking and fraud. The outcome of the election did a little bit to ease concerns about these worries, especially on the hacking front. Partisan divisions continued when it came to attitudes about fraud; attitudes were less structured along party lines, and were more likely to change after the election, when it came to hacking.

This is the last in a series of essays I have posted that have contrasted attitudes about the conduct of the 2018 election, comparing the pre- and post-election periods. A few days ago, I looked at the broad question of voter confidence. and the (possible) demise of the “winners effect.” Before that, I took at look at the narrower question of confidence in preparations to counter cyber threats in the election.

The data in this post were taken from two surveys I conducted, one before the election (during June 7-11) and one after (during November 7–9). In each case, the surveys interviewed 1,000 adults as a part of the YouGov Omnibus survey. The research was supported by a grant from NEO Philanthropy, which bears no responsibility for the results or analysis.

Fraud, Suppression, and Hacking

Elections are complicated stories. During the conduct of an election, claims are regularly made in an effort to set the public’s expectations about whether the outcome will be, or was, fair. In recent years, these claims have gotten more insistent and sharper, but they have been part and parcel of election contests for centuries.

At the risk of over-simplifying, in 2018, three topics showed up in the news on a regular basis that bore on the conduct of the election and its fairness. The first was fraud, or the idea that the wrong people — immigrants, double-voters, and the like — were illegally voting. The second was suppression, or the idea that efforts were being made by officials to discourage voting by people because of their race or party. The final was hacking, or the idea that computer equipment used to administer the election was being tampered with.

We can further divide this last topic in two, by distinguishing between tampering with the computer systems running the election, such as voter registration systems, and the voting machines used to cast and count ballots.

To gauge worries about these topics, in June and in November (after the election), I asked the following battery of questions:

Many people worry that elections might be tampered with, because of the illegal or unethical actions of others. The following is a list of four ways that bad actors might try to tamper with elections. [June question] How much of a problem do you consider these to be in a typical election in the United States? [November question] How much of a problem do you consider these to have been in the recent midterm election nationwide?

- Tampering with the computers used by election administrators to run elections [Computer tampering]

- Tampering with the voting equipment used to cast or count ballots [Voting machine tampering]

- People trying to vote even though they are too young, don’t actually live in the precinct, or are non-citizens [Voter fraud]

- Officials trying to keep people from voting because of their party membership or race [Voter suppression]

The response categories were “major problem,” “minor problem,” “not a problem,” and “don’t know.”

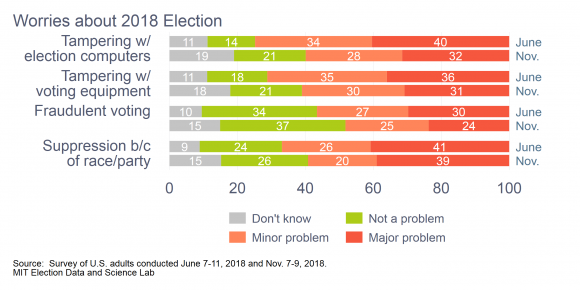

In June, the biggest perceived problems were tampering with the computers used to run elections (40% “major problem” ) and suppression (41%), followed by tampering with voting machines (36%) and voter fraud (30%). (Click on the accompanying graph to emlargify it.)

In June, the biggest perceived problems were tampering with the computers used to run elections (40% “major problem” ) and suppression (41%), followed by tampering with voting machines (36%) and voter fraud (30%). (Click on the accompanying graph to emlargify it.)

With the November election, attitudes moved in two directions. On the one hand, more people responded that they didn’t know the answer to the question. Whether this reflects an actual change in attitude, or is an artifact of the survey method and the slight change in questions between the two administrations, remains to be explored.

On the other hand, respondents generally eased their concerns over whether hacking, fraud, or suppression were problems. These are not huge shifts, but they are consistent, for instance, with my previous finding that respondents became more confident in cyber-preparedness over time.

The role of party

Party is the big independent variable these days, so it’s natural to explore partisan differences in these answers. Democrats have run on an anti-suppression platform in recent years, while Republicans have been vocal in suggesting that fraud is the election problem to be worried about.

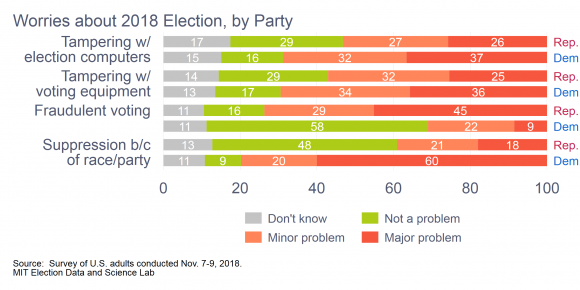

Thus, it’s not surprising that these partisan differences showed up in answers to these survey questions, especially the questions pertaining to fraud and suppression.

Thus, it’s not surprising that these partisan differences showed up in answers to these survey questions, especially the questions pertaining to fraud and suppression.

In the November survey, for instance, 58% of Democrats stated that voter fraud had not been a problem in the 2018 election, compared to only 16% of Republicans. In contrast, 48% of Republicans said that suppression was not a problem, compared to only 9% of Democrats.

There were also partisan difference on the two hacking questions, although they weren’t as stark. For instance, Republicans were more likely to state that tampering with computers used to administer elections was not a problem, by a 29%-16% margin, and that tampering with the voting machines was not a problem (29%-17%). This partisan difference shouldn’t surprise anyone who has followed these issues, but it also bears emphasizing that there is much greater variability in attitudes about hacking within the parties than there is about fraud and suppression.

So much for November attitudes. How did attitudes change from the summer?

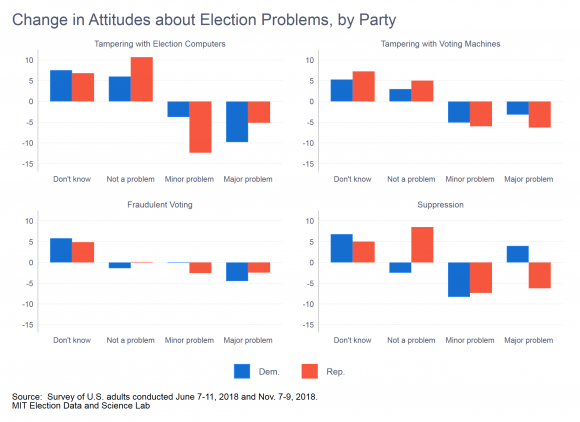

Here, it really matters what the question is. Both Democrats and Republicans became less likely to state that hacking of either sort was a problem, after the election had been conducted, although the change was greater in reference to administrative computers compared to voting machines.

Here, it really matters what the question is. Both Democrats and Republicans became less likely to state that hacking of either sort was a problem, after the election had been conducted, although the change was greater in reference to administrative computers compared to voting machines.

On the question of fraud, the outcome of the election did little to change attitudes among members of both parties.

However, on the issue of suppression, we see some interesting variation and distinction between the parties. Republicans became much less likely to regard suppression as a problem, either a major or minor one, when the question was asked in November, compared to June.

Among Democrats, the fraction saying that suppression was a minor problem fell between June and November, with a slight increase coming among those who said it was a major problem, plus, of course, the increase in the number of people who stated they didn’t know the answer to the question.

Some final thoughts

The purpose of these surveys was to take the pulse of voters, and not to probe these issues deeply. Therefore, unfortunately, it’s not possible to probe deeply the nature of partisan changes since the summer.

One observations seems obvious to probe in the future, as better and deeper data come available. Among the four topics explored in these surveys, the issue of voter fraud is probably the most long-standing. Party divisions were big in June, and they didn’t budge much because of the election.

The other three issues are more emergent. In the case of suppression, Democrats have certainly been pressing the issue for many years. In contrast, it’s possible that Republicans just haven’t been paying much attention. Thus, it is possible that news from states like Georgia and Florida in the days immediately before and after November 6 primed a partisan response, especially among Republicans. (Democrats were already there.)

The issue of election hacking has emerged in a context of difficult-to-parse claims that evoke attitudes of patriotism, partisanship, and acceptance of technology. Because the 2018 election ended up being relatively quiet when it came to news of verified cyber attacks on the system, it’s to be expected that Election Day brought relief among voters of all types.

Had there been a major verified cyber attack, the attitudinal patterns would probably have been considerably different. Consider, for instance, what would have happened if the Broward County election-night reporting system had been hacked into. Of course, the important thing for the conduct of the election is that it wasn’t hacked into. But, the important thing for understanding public opinion about election hacking is that 2018 did not test the system like 2016 did, or like 2020 might.

In the coming months, much more comprehensive public opinion data will become available from the 2018 election that will allow more in-depth exploration of the issues I have written about in Election Updates, here and in past weeks. (The recent release of a great report by the Pew Research Center on some of these issues has left me champing at the bit to gain access to the raw data, once it comes available.) Until then the equivalent of the election geek hot-stove league will have to chew over the evidence we do have, as we look forward to the spring and even better public opinion data on these issues — not to mention the promise of baseball.