To continue on this past week’s “all things Virginia” theme in election geekery, let’s take a look at absentee voting in the Old Dominion in last Tuesday’s election.

Two things make absentee voting in Virginia interesting, at least to me. The first is administrative — where were absentee votes cast? The second is political — did they skew Democratic or Republican?

The administrative take

Like most of the eastern U.S., Virginia continues to require an excuse to cast an absentee ballot. Virginia’s list of excuses is pretty long — the absentee ballot application form lists 20 different excuses. Still, the vast majority of Virginia’s voters cast ballots on Election Day — 6% in 2016, compared to the nationwide rate of 21%.

Despite its relatively traditional absentee ballot law, many of Virginia’s registrars have been trying to increase the amount of absentee voting, both to give their voters more options, and to relieve pressures on the traditional polling places. (There is good reason for this latter goal, since Virginia had among the longest Election-Day wait times in 2012.) In some counties, satellite locations have been established to receive absentee ballots, which means that there is little difference in practice between early voting and absentee voting in some places.

The registrars’ efforts are helped by the fact that one of the reasons that an absentee ballot can be cast is if the voter has “business outside the county/city of residence on Election Day.” Considering that the Census Bureau reports that 52% of Virginians work in another county than where they live, the possibilities would seem to be substantial.

Despite the possibilities, the fraction of Virginia voters choosing the absentee route was relatively low in 2017 — only 7.1%, up from 5.4% in the last gubernatorial race, to be sure, but still low compared to states with no-excuse absentee voting.

The rate of absentee ballot usage wasn’t uniformly low this year, however. Nearly 21% of Falls Church’s voters, for instance, cast an absentee ballot, as did 14% of Arlington’s.

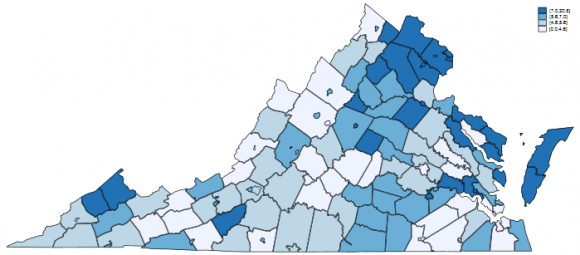

The following map shows the rate of absentee ballot usage across the state. (Click on the map to see a larger version.) On the whole, more absentee ballots were cast in Northern Virginia than in the rest of the state — with a few other hot spots here and there.

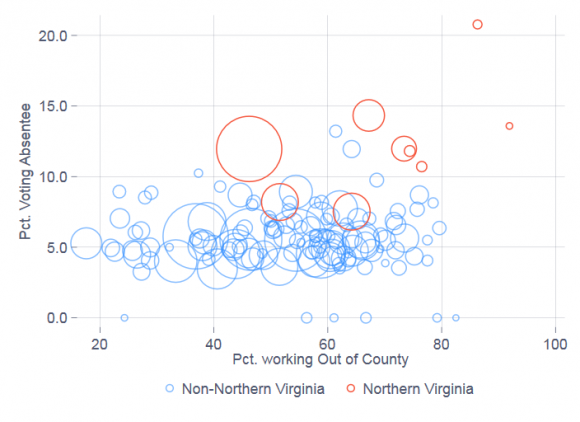

With Virginia’s absentee law favoring voters working out-of-county, and so many Northern Virginia voters working in the District of Columbia, one might predict that absentee ballots were more likely to be used where there were a lot of cross-county commuters.

But, this prediction turns out to be incorrect, as is illustrated in the accompanying scatterplot, which shows the relationship between the percentage of ballots cast absentee (y-axis) and the percentage of workers commuting out of the county. Whatever weak relationship does exist is due entirely to two small independent cities in Northern Virginia, Falls Church and Manassas Park, nearly all of whose residents work outside their home city.

But, this prediction turns out to be incorrect, as is illustrated in the accompanying scatterplot, which shows the relationship between the percentage of ballots cast absentee (y-axis) and the percentage of workers commuting out of the county. Whatever weak relationship does exist is due entirely to two small independent cities in Northern Virginia, Falls Church and Manassas Park, nearly all of whose residents work outside their home city.

In fact, the strongest factor predicting the rate of absentee ballot usage appears to be living in northern Virginia, where the absentee usage rate was twice that of the rest of the state — even when controlling for commuting patterns.

The political take

The second take on absentee voting in Virginia is political. Since at least the 2008 presidential election, turning out one’s most ardent supporters early in the process has been a standard tactic of most well-funded campaigns. There is also a bit of folk wisdom that says that the side with the most riled-up base will have an advantage in the early voting (or absentee) phase.

Democrats did win the absentee vote in Virginia, and by a comfortable margin — Ralph Northam won 59% of the absentee votes cast, compared to 53% of on Election Day. That would suggest that absentee voting in Virginia was a predominantly Democratic tool in 2017.

The problem with this suggestion, however, is that the rate of absentee ballot usage was greatest in Northern Virginia, which was also the most pro-Democratic part of the state. Thus, the higher percentage of votes cast for Northam among absentee voters could just be another way of saying that Northam received more votes in Northern Virginia.

The actual partisan pattern of absentee voting becomes interesting when we ask where Democrats did better (or worse) on a more local level. We can do this first by plotting the percentage of absentee votes that were cast for Northam against the percentage of Election-Day votes he received in each county. That is the accompanying scatterplot. Note that Northam’s absentee vote out-performed his Election Day vote in most counties, but particularly in the smaller counties of the state where the Republican nominee, Ed Gillespie, did best on Election Day.

The actual partisan pattern of absentee voting becomes interesting when we ask where Democrats did better (or worse) on a more local level. We can do this first by plotting the percentage of absentee votes that were cast for Northam against the percentage of Election-Day votes he received in each county. That is the accompanying scatterplot. Note that Northam’s absentee vote out-performed his Election Day vote in most counties, but particularly in the smaller counties of the state where the Republican nominee, Ed Gillespie, did best on Election Day.

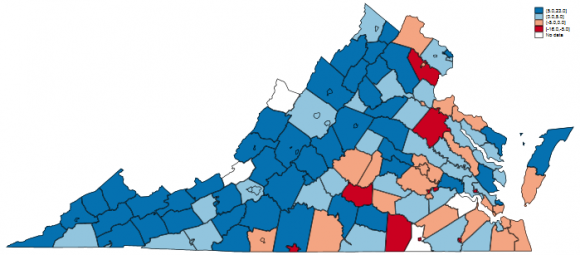

The second way to do this is by mapping the difference in Northam’s percentage of the vote, comparing absentee ballots with Election Day ballots. This is done in the following map. (Blue jurisdictions gave Northam a bigger percentage in the absentee vote, while red jurisdictions gave Gillespie a bigger absentee vote percentage.)

Thus, while Northam did win the absentee vote to a greater degree than he won the Election Day vote, this appears to be primarily an artifact of his strength in northern Virginia, which was both heavily Democratic and voted absentee more so than the rest of the state. From the perspective of individual Democrats, the absentee route was more likely to be chosen by those in the more conservative parts of the state than in the D.C. surburbs.