Our Monitoring the Election project has released two briefs, reporting on preliminary results from a national survey of registered voters conducted immediately after the November 3, 2020 Presidential Election.

These two briefs provide a glimpse into how the heated rhetoric about election and voter fraud before and during the general election has been received by the American electorate.

One of these briefs focuses on the general question of voter confidence in the election.

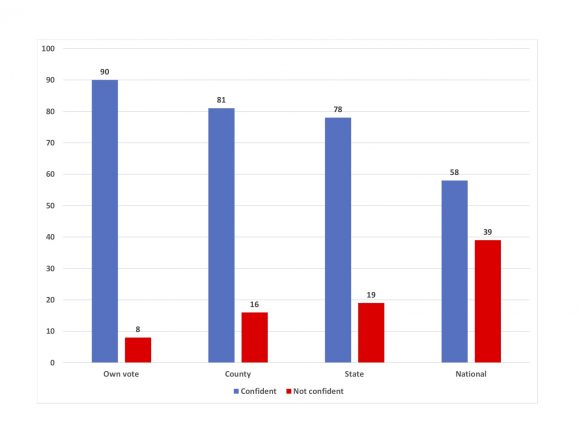

We asked registered voters to answer four questions about their confidence regarding the 2020 presidential election: their confidence that their own ballot was counted as intended (asked to registered voters who cast a ballot), and their confidence that ballots were counted in their county, their state, and across the nation (the latter three asked to all registered voters). The topline results are shown in this graph from the report.

As you can see, 90% of voters were confident that their ballot was counted as they intended, which given the heated rhetoric about this election is a remarkable number. It’s also remarkable that about eight of ten registered voters have confidence that votes were counted as intended in their counties and their states. Those are also remarkable numbers, and in my opinion, a strong indication that American voters are overall quite confident that their local and state election administration was handled well in this contested election.

But when we get to the national level, we find that just over a majority of American registered voters (58%) were confident about the administration of this fall’s election, and that 39% lacked confidence (the remaining registered voters didn’t have an opinion). This lower level of confidence about the national administration of the election is concerning.

Digging one layer deeper into the data, we looked at perceptions of confidence by partisanship and presidential vote. We see high levels of confidences for both Republicans and Democrats, and for both those who voted for Trump or Biden. Nearly every Democratic voters (and nearly every Biden voter) in our sample was confidence that their own ballot was counted as intended: 86% of Democrats were confidence, and 97% of Biden voters were confident. Among Republicans confidence in their own vote was high, with 85% of Republicans and 84% of Trump voters confident in their own vote being counted.

But moving to the national level, the sharp degree of partisan polarization in the United States emerges: while many Democratic and Biden voters were confident about the administration of the election nationally (84% among Democrats, and 87% among Biden voters), most Republicans and Trump supporters lacked confidence in the national administration of the election, with 66% of Republican registered voters lacking confidence, and 70% of Trump voters lacking confidence in the national administration of the vote.

The other brief, authored by Yimeng Li, focuses on a number of questions in the survey asking registered voters about their perceptions that various types of election or voter fraud might occur, and also about hacking of the voting technology in the 2020 election. The survey included questions asking whether the respondent thought that various types of election or voter fraud were common or not:

- Double voting.

- Stealing or tampering with voted ballots.

- Voter impersonation.

- Non-citizen voting.

- People voting absentee ballots of other voters.

- Officials changing reported vote counts in a way that is not a true reflection of how the ballots were actually counted.

Yimeng found that there is a sizable proportion of the American electorate that believes that voter or election frauds like these occur or are common. To quote from the report:

There are many registered voters nationally who said that election or voter fraud

is very common (between 12% and 17% for different types of fraud) or occurs

occasionally (15-17%). Ballot stealing or tempering, fraudulent casting of absentee

ballots intended for another person, and non-citizen voting are perceived to be the

top three types of election or voter fraud. Only about half of the voters believe each

of the six types of fraud occurs infrequently or almost never.

Like we saw regarding voter confidence in the 2020 Presidential election, the perceptions of the American electorate are very polarized along partisan lines. Across the six different types of election or voter fraud we asked about in the survey (Table 2 of the brief), we generally see that majorities of Biden voters believe that these types of fraud are infrequent or that they never occur, while majorities of Trump voters believe that these types of fraud are very common or that they occur occasionally.

A good example of this regards non-citizen voting. Sixty-six percent of Biden voters said that non-citizen voting almost never occurs, while another 12% said it occurs infrequently. On the other hand, 35% of Trump voters said that non-citizen voting is very common, and another 25% said that it occurs occasionally. That’s a pretty stark partisan different in perceptions of the incidence of non-citizen votes.

So what does this all mean, in particular for future elections in the United States?

It seems clear from these topline estimates from this survey that the American electorate remains confident that their own votes were counted, and that they are quite confident that votes in their counties and states were counted as intended. Which is a good sign.

But we see much less confidence in the national administration of the election, where opinions are deeply divided on party lines. We also see that a reasonably large segment of the electorate believes that various types of election or voter fraud occur, and that perceptions about the incidence of election fraud are polarized by partisanship.

This indicates that voters are picking up on elite partisan rhetoric about election and voter fraud, which have been going on since 2016, and which of course has intensified in the past few weeks. But does this mean that despite high levels of voter participation in the 2020 presidential election, will those who lack confidence or are concerned with fraud might be less likely to vote in future federal elections (for example, the 2022 and 2024 elections)? Will the lower levels of confidence in the national administration of federal elections, and concerns about election fraud for some segments of the electorate, lead to further erosion of trust in American democratic institutions?

At this point it’s hard to know what might happen. But these survey results provide some cause for concern, and they show that we need to continue our work to inform the American electorate about the integrity of the 2020 presidential election.

We’ll be posting additional briefs from our survey in coming days and weeks on our website.