Charles Stewart III, MIT

[Note: This posting was written on the eve of Election Day, based on statistics reported Monday morning.]

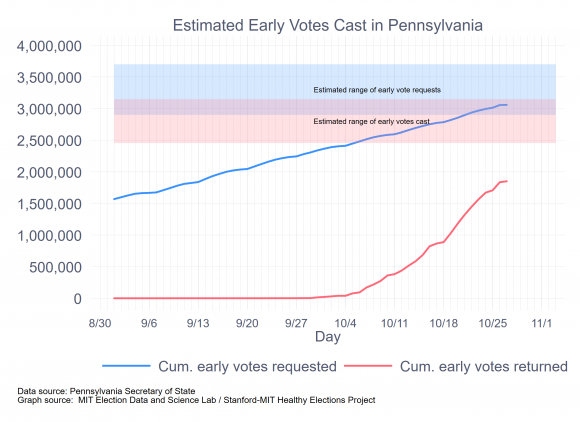

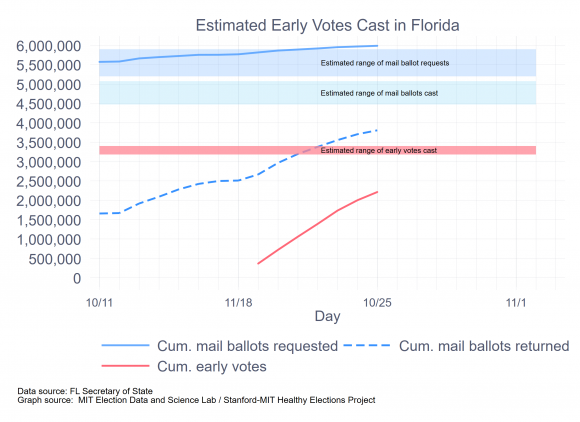

We’ve come to the end of the time in the election cycle when the politically engaged, tired of obsessively going to FiveThirtyEight or the Silver Bulletin, look to other tea leaves. A few of you may still wonder what the mail and early in-person voting trends portend for the results tonight. Here are some thoughts on that.

(Before proceeding, a little nomenclature: Some people—journalists, election officials, and just normal folks—mean different things when they say “early voting.” When some refer to early voting, they mean any votes cast before Election Day, whether cast in person or at home. Others only mean votes cast in person. To try to avoid that confusion here, I will refer to the in-person version as “early voting,” and combined early in-person and by-mail voting as “advance voting.” I will refer to ballots cast after being mailed to a voter as “by-mail ballots.” )

My simple answer to the “what does this all mean” question is that things seem to be returning to normal in two related ways. First, voters are mostly returning to pre-pandemic voting patterns (with important exceptions). Second, campaigns are recognizing they need all the turnout weapons in their arsenal to win.

2024 represents the return to a long-term trend of increased advance voting

First, the patterns of the use of vote modes. As illustrated in the graph below, prior to 2020, the fraction of people voting on Election Day had been declining linearly for a quarter century, replaced in equal measure by people voting by mail and voting early. This pattern was interrupted by the pandemic, which shifted large numbers of voters out of Election Day voting booths into other modes, especially voting by mail. In 2022, mode usage either returned to the pre-pandemic trend or at least was much closer to the trend. (By-mail voting was about 5 points above trend in 2022, while early voting would have been right on trend if we account for the obvious seesaw pattern in the data between on- and off-year elections.)

The dashed lines in this graph are based on simple linear trends in the use of the three voting modes from 1996 to 2018, estimated using linear regression. Although the trends are based on the data from 1996 to 2018, they have been extended to 2024 to see how the pandemic and the recovery from it affected the long-term trends.

Not surprisingly, in 2020, Election Day voting was significantly below trend, while by-mail voting significantly exceeded it. Early voting was roughly what we would have expected without the pandemic. In 2022, Election Day voting returned us to where the long-term trend predicted; early voting was slightly below the trend, and mail voting slightly exceeded it.

The ends of the trend lines provide the predictions of mode usage in 2024 if we just allow the pre-pandemic trends to continue. This is obviously a mindless prediction, if you want to call out-of-sample prediction using regression mindless, but it does help define the expectations ballpark for this year.

Keep in mind that most states made changes to their laws that either facilitated or reined in advance voting before 2022, so state-law-induced factors weighing on 2024 are already baked into the trends for the most part. The decision by Republican strategists to validate advance voting in 2024 may have played a role in the growth of voting in the pre-Election Day period this year. Still, the shift could also have reflected voters deciding how they prefer to vote, given what’s going on in their lives.

As voters shift to early voting in 2024, they are also shifting away from by-mail voting, compared to 2020. Based on Michael McDonald’s indispensable early voting website and some back-of-the-envelop calculations of my own, it appears we are on target for over 40 million early votes in 2024, up from 36 million in 2020, and 48 million by-mail votes, down from 66 million in 2024. Both of these numbers are right where the trend lines in the above graph would predict if turnout ends up at around 160 million. This also means that 2024 may be the second election in a row in which most votes are cast before Election Day. (It will at least be close.)

The closing partisan gap

Of some note, in 2024, there has been a shift in thinking among Republicans about the value of voting by mail. Certainly, the GOP and its candidates are giving mixed signals about advance voting. Still, just as Donald Trump’s attack on by-mail voting helped create a partisan chasm in voting by mail in 2020, his campaign’s change of attitude in 2024 has to make a difference, too.

For the decade before 2020, Democrats were only slightly more likely to vote by mail than Republicans, and almost all that difference was accounted for by the greater availability of no-excuse absentee voting and universal vote-by-mail in predominantly Democratic states. As the graph below shows, in 2020, a gap of nearly 30 points opened up between Democrats and Republicans in usage rates of by-mail ballots. That gap was then cut down to 12 points in the 2022 midterm.

It appears that the gap has been diminished even further in 2024, although we cannot be 100% certain about how much. The party statistics reported by the states and communicated by Michael McDonald reflect the party registration of those returning ballots in states that record party registration. We won’t know for sure about the size of the partisan gap until surveys that track such things begin to report their results.

An increase in Republican by-mail voting in 2024 could just represent the demise of the stigma associated with mail voting. A decline in the use of by-mail voting by Democrats could also just represent a weakening of the sense that voting by mail is part of one’s Democratic duty.

Of course, it could be that a decline in advance voting by Democrats in comparison to Republicans could reflect a better mobilization effort by the Trump campaign and a lagging effort by Republicans. I’m doubting it, though. If I were a betting person, my money would be on voters and campaigns getting closer to a pre-pandemic normal. By Tuesday night, we’ll see if I’m right.