In my last posting of this series, I presented some high-level statistics about the population dynamics associated with the administrative challenges of voter registration, such as

- 250 million people of voting age

- 230 million eligible voters

- 204 million registered voters

- 147 million movers on a four-year basis

- 10 million deceased on a four-year basis

Numbers such as these are valuable for gaining an understanding of the magnitude of the voter registration challenge. But, are they accurate?

This question of accuracy has come up recently as election officials have been challenged by PILF and other groups over whether election agencies are diligently removing ineligible voters in a consistent manner. Beyond that controversy, the value of releasing registration statistics to the public is that it increases transparency by adding another set of eyes to the registration process. If the data can’t be trusted, however, we need to reconsider how well the registration process can be overseen by the public.

The most direct way to use voter registration statistics is to see if everything adds up, much like we expect a financial balance sheet to be internally consistent. Is the number of registered voters this year equal to last year’s number, net of additions and subtractions over the subsequent year? A more nuanced way to scrutinize voter registration statistics is to compare them to independent population numbers, such as is done with registration totals, which are compared to the size of the voting-age population.

Over the next two posts, I will start with the voter registration statistics themselves. In subsequent posts, I’ll consider the population statistics they might be compared to, such as voting-age population.

Today, I address two questions:

- Where do voter registrations come from?

- How accurate are the registration rolls?

In the next installment, I will take on the following questions:

- How many people are registered to vote?

- How accurate are statistical reports about voter rolls?

Where do voter registrations come from?

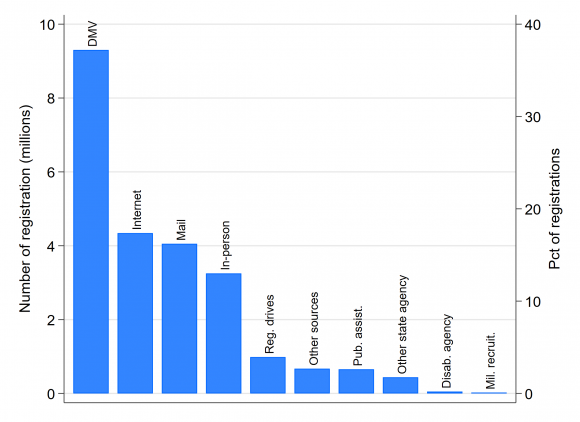

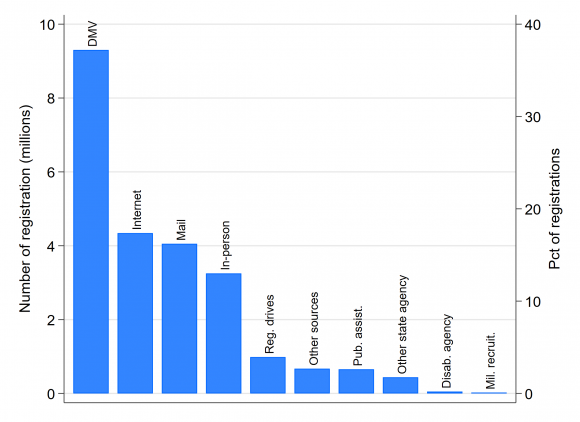

Election agencies are the custodians of voter rolls, and thus registration statistics. However, relatively few registrations occur at election departments. Every two years, when the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) files its report to Congress about implementation of the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), it provides the sources of new registrations, as reported by the states. As the accompanying figure shows, in the 2015-2016 report, the most common source of the nation’s 29 million new voter registration applications was motor vehicle agencies (DMVs), which supplied 39% of new registrations. Just 14% of registrations occurred in-person. (Click on the graph to get a larger view)

Election agencies are the custodians of voter rolls, and thus registration statistics. However, relatively few registrations occur at election departments. Every two years, when the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) files its report to Congress about implementation of the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), it provides the sources of new registrations, as reported by the states. As the accompanying figure shows, in the 2015-2016 report, the most common source of the nation’s 29 million new voter registration applications was motor vehicle agencies (DMVs), which supplied 39% of new registrations. Just 14% of registrations occurred in-person. (Click on the graph to get a larger view)

(These statistics are based on the sources of registrations reported by states; registrations that are not attributed to a source are excluded from the percentage calculations. Nearly 18% of the new registrations were not attributed to a source, which is a sign that voter registration statistics reported by the states to the EAC are not always forthcoming. In the 2015-2016 NVRA report, eight states failed to report the sources of registrations altogether, and one only reported the source of about half. This isn’t evidence that the underlying registration records themselves are inaccurate, but it is of concern among those who believe that public reporting is an important source of accountability in the maintenance of voting rolls.)

Between 2015 and 2016, 15% of all new registrations came through the Internet, even though barely half of the states allowed registration via the Internet. As the number of states offering Internet voter registration grows, it’s reasonable to expect the Internet to rival DMVs as the top source of new registrations.

How accurate are the registration rolls?

If the voter rolls are inaccurate, their usefulness is diminished — voters and poll workers face hassles at the polls, polling places are inadequately supplied with ballots, voter information pamphlets are mailed out wastefully, etc. However, it’s not clear precisely how accurate the lists are — there are no commonly accepted auditing standards, and the results of the audits that do occur are rarely publicized.

The 2016 Survey of the Performance of American Elections (SPAE) provides one answer to the question of how accurate the voter lists are. Of the respondents who voted in person, 2.2% said they encountered a registration problem when they went to the polls.

The SPAE responses are consistent with the number of provisional ballots cast in 2016. Provisional ballots are intended as a safety net when rolls are inaccurate, and so might be used as a proxy to indirectly gauge the accuracy of voter lists. According to the EAC, about 2.5 million total provisional ballots were cast in 2016, which is about 1.8% of turnout.

This 1.8% rate of provisional ballot use might be taken as an upper bound on the rate of severe errors on the lists. I say “upper bound,” because some states use provisional ballots just to update address changes — it’s not clear if these should be counted as errors — or to handle an in-person voter who had been sent an absentee ballot. I say “severe error,” because without access to a provisional ballot, many of these voters would have been turned away at the polls, without even a chance to vote.

On the other hand, about a dozen states offer election day registration. In those states provisional ballots are much less likely to be used because registration problems are often resolved by the voter registering on the spot and then casting a ballot.

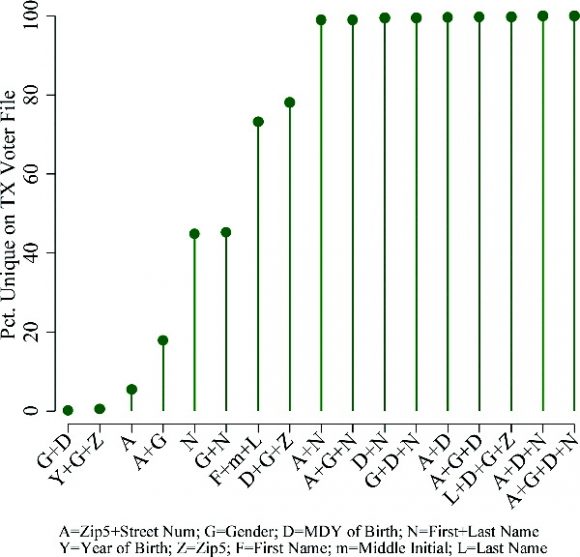

Not all errors are severe enough to prevent voters from voting, but they could be serious enough to cause other administrative problems. They might also cause a false match if one were comparing voter registration rolls from two states.

One important error relevant to interstate matching is birth-dates. It is a little-known fact to the general public that voter registration files sometimes have placeholder birth-dates. Some voter registration systems in the days before computers didn’t retain the birth-date of the voter. Nowadays, even when the systems retain birth-dates, the elections department might fail to record the birth-date (or the birth-date might be illegible on the registration card). In either case, if a birth-date is missing, something is usually entered into the database. Most commonly, that date is January 1, 1900.

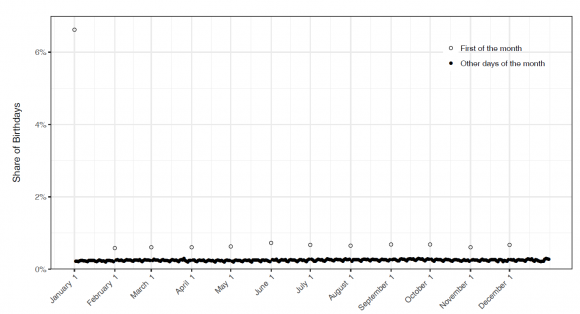

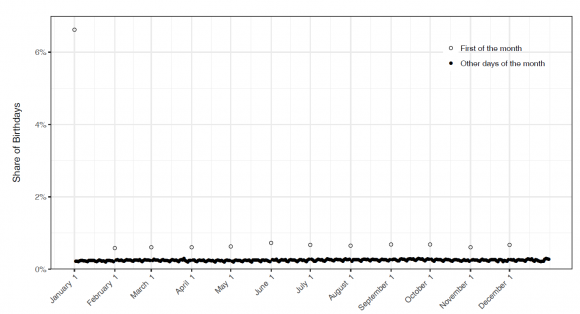

A multi-campus team of researchers recently conducted research that shines light on this form of the birth-date problem. Using a nationwide voter file supplied by a political firm, they calculated the number of people born on each day in 1970 who appeared in the file. This is what the distribution of birth-dates looked like (Click on the graph for a larger view.):

Clearly, 6% of all voters born in 1970 weren’t born on January 1.

If we consider the purpose for which voter registration lists were constructed, birth-date errors are relatively benign — once you’ve turned 18 years old, you’ll always be at least 18. The problem of birth-date errors becomes more important when the voter lists are used for another task, such as cross-state matching.

(Note: The problem of birth-date errors is separate from another issue raised in this research paper, which is that actual birth dates aren’t uniformly distributed. More births occur on weekdays than on weekends, for instance. Furthermore, some names, such as Jesus and Carol, are given to children born disproportionately on certain dates. The clumping of birth-dates, either because of error or other factors, increases the likelihood that cross-state database matching that uses birth-dates will produce false positives, that is, match registration records that appear to be of the same person, but in fact are different people.)

Another team of researchers conducted a study of the accuracy of voter files in L.A. County and Florida following the 2008 election. The study involved mailing letters to a sample of voters and asking them if the information on the voter rolls about them was correct. The details of the findings are too numerous to review here. But, among other things, 5% of the L.A. County birth-dates needed to be corrected, while only 0.3% in Florida. In Florida, 3.5% of the sampled voters stated that their race was incorrectly recorded. (California doesn’t record the race of voters.) In L.A. County, 3.6% of addresses needed updating, compared to 3.8% in Florida.

The answer to the question, “how accurate are the registration rolls?” appears to be “about as accurate as they need to be, given what they were designed for.” Because they were designed to help facilitate voters gaining access to ballots and managing other details of voting such as allocating voters to precincts, the small fraction of inaccuracies in items like name and address can normally be dealt with using provisional ballots. Voter files were not designed for the purposes of interstate matching. That is one reason that simple name + birth-date matches tend to yield so many false positives, that is, matches that appear to link the same person to two states’ voter lists, but in reality are inaccurately linking two different people.