I was quoted this morning in a story by Alexa Olgin from WFAE in Charlotte about the start of early voting in North Carolina. This gives me a chance to dig out some old research I’ve done on the North Carolina legislature’s past actions to restrict early voting hours in the Tar Heel State, and to state why I believe the most recent change in early voting hours will inconvenience voters and waste local tax dollars.

(Nomenclature note: North Carolina refers to early voting as “One-Stop” absentee voting. Here, I use the more common colloquial phrase.)

Last summer the legislature changed North Carolina’s early voting law to mandate that all early voting sites that are open on a weekday have the same hours, 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. Supporters in the legislature maintained that the purpose was to reduce confusion about when polling places would be open.

Unfortunately, in all likelihood, the law will increase congestion (again) during early voting.

A Little Throat Clearing to Begin

Before proceeding, I need to lay out two facts, in the interest of full disclosure.

First, as almost everyone reading this blog knows, my major message in the elections world is that data’s our friend. Whether voters are confused about early voting times in North Carolina is an empirical question. I know of no direct evidence on this point. The fact that North Carolina was fourth in the nation in 2016, in terms of the fraction of votes cast early, suggests that a lot of voters have figured it out.

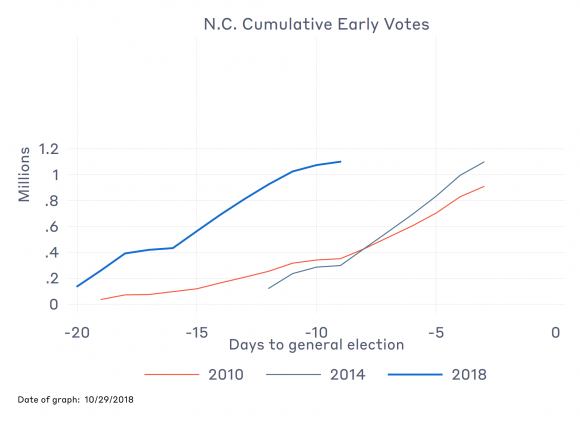

In the face of limited (if any) direct evidence of early voting confusion, we have to weigh the practical impact of requiring uniform hours that stretch for 12 hours starting at 7 a.m. In 2014, when counties were essentially required to do the same thing, relatively few voters took up the counties on their offers to vote earlier and later in the day. It’s likely the same will be the case in 2018.

Second, as some people don’t know, I served as an expert witness on behalf of the U.S. Department of Justice when it sued the state over changes to its voter laws in 2013, including a reduction in the number of days available for early voting. In my role as expert, I filed a few reports about the likely effects of changing the early voting laws. You can read the relevant reports here and here.

The New Law Mandates Early Voting Sites Be Open at the Wrong Times

To continue.

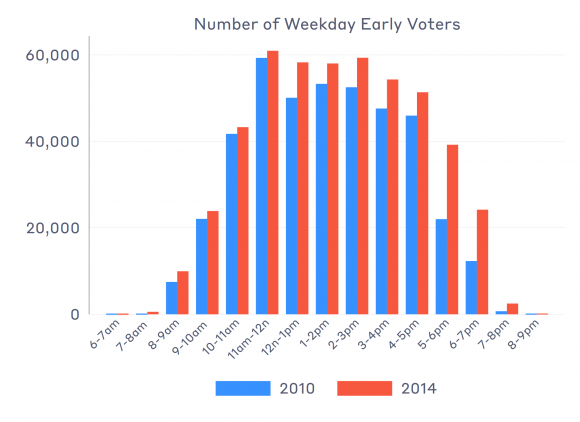

What is wrong with mandating that all early voting times maintain uniform hours of 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.? The main problem is that most early voters don’t utilize the earliest and latest hours of early voting. In both 2010 and 2014, the last two midterm elections, three-quarters of weekday early votes were cast between 10 a.m. and 5 p.m.; 90% were cast between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m.

Readers may recall that North Carolina’s legislature passed a law in the summer of 2013 (HB 589, or VIVA, for “Voter Information Verification Act”) that reduced the number of early voting days from 17 to 10. It also required that counties maintain the total number of hours of early voting in 2014 as they had in 2010.

The law was invalidated by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ahead of the 2016 election, but was in effect for the 2014 election. Thus, we can see what happened the last time the legislature tried to mandate to the counties when they offered early voting.

(For readers desiring to know more about the details of the law’s change and effects, check out this recent article by Hannah Walker, Michael Herron, and Daniel Smith in Political Behavior. In contrast with this post, the Walker, Herron, and Smith article focuses on changes in 2016.)

Counties could do one of three things to comply with VIVA’s early voting provisions. First, they could ask for a waiver, and not offer as many hours in 2014 as in 2010. Second, they could just increase the number of hours their early voting sites were open without adding any additional sites. Third, they could increase the number of early voting sites and keep the hours the same.

What did the counties do? A few requested, and were granted, waivers. On the whole, though, counties adopted a mix of the last two strategies, although it was heavily weighted toward expanding and shifting hours in existing sites.

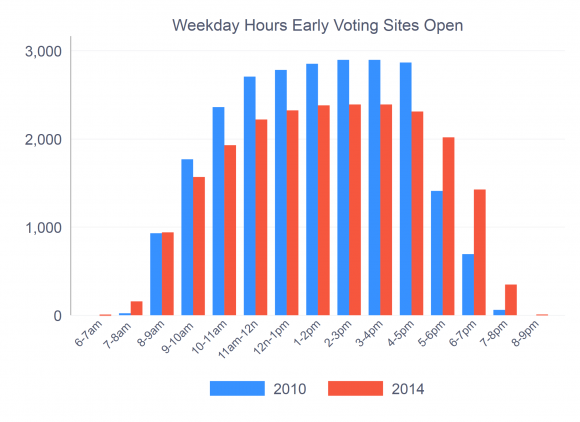

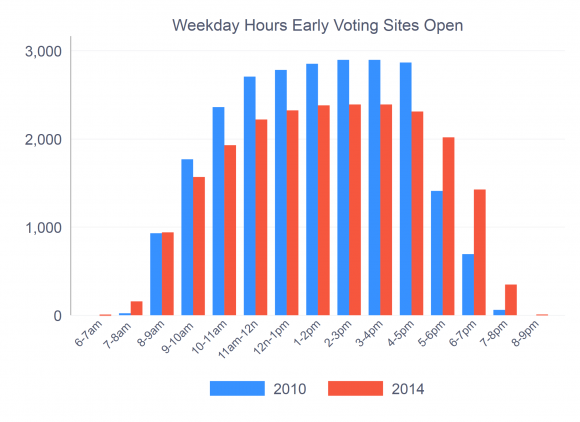

First, the number of hours allocated to weekends increased by 55% while the number of hours allocated to weekdays declined by 7.6%.

Second, weekday hours were shifted from the 9-to-5 period to either very early (6-9 a.m.) or very late (5-9 p.m.). The number of hours allocated to the 9-to-5 period fell 17% while the number of before-work hours grew 15% and the number of after-work hours grew 7.2%. (The accompanying figure shows the distribution in the hours offered on weekdays to early voters between the two years. Click on the image to biggify.)

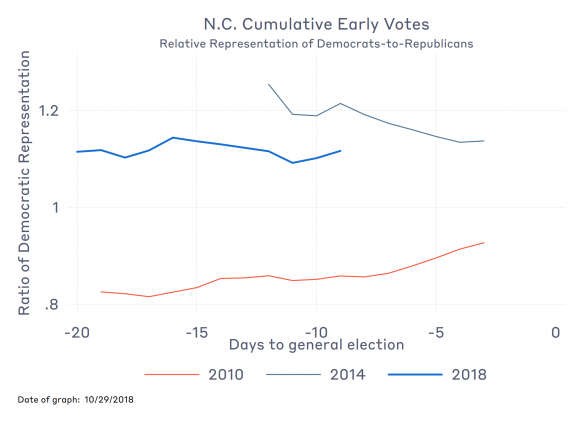

Did early voters respond by “going to where the hours were?” Yes and no.

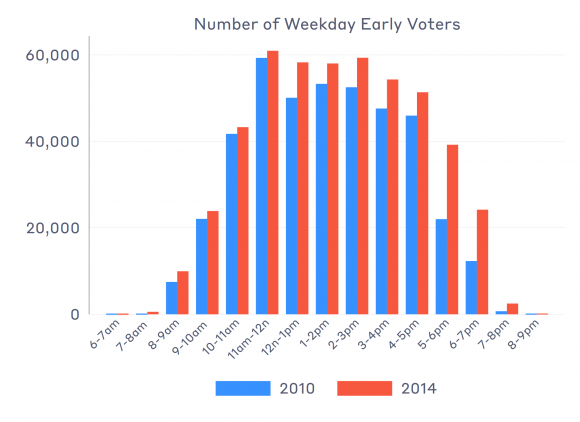

The accompanying figure shows the hours of the day when early voters cast their ballots in 2010 and 2014. It is true that many more early voters cast ballots after 5 p.m. in 2014 than in 2010. It is also true that more early voters cast ballots during the 9-to-5 period, as well — the period when counties cut the number of hours.

The accompanying figure shows the hours of the day when early voters cast their ballots in 2010 and 2014. It is true that many more early voters cast ballots after 5 p.m. in 2014 than in 2010. It is also true that more early voters cast ballots during the 9-to-5 period, as well — the period when counties cut the number of hours.

The result was that the state did not meet the demand for early voting when the voters wanted it. Between 2010 and 2014, the number of 9-to-5 early voters increased by 9.9%, despite the fact that the number of hours offered for early voting fell by 17% during these hours.

The result was to create an over-supply of voting times available for after-hours voters while doing nothing about the under-supply of mid-day times, or reducing the over-supply that already existed for voting very early in the morning.

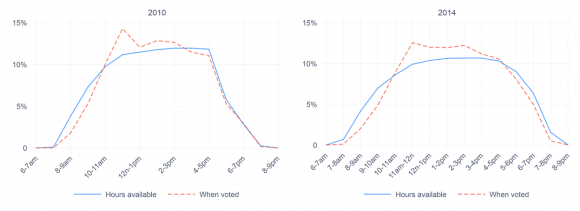

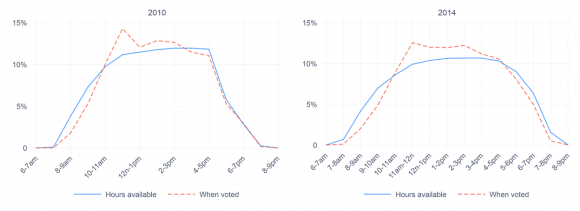

This mismatch of the supply of early voting hours with demand is illustrated by the following graph, which compares the distribution of times when early voters cast their ballots with the distribution of times when the early voting sites were open. Note that in 2010, hours available exceeded voters voting up through 11 a.m., at which point the ratio of available hours-to-voters shifted. This imbalance remained until around 3:30, when supply-and-demand evened out.

In 2014, the over-supply of early-morning hours actually increased a bit while the under-supply of early-voting hours remained. And, what had been a good match between supply-and-demand after 5 p.m. became an over-supply of available hours in 2014.

In short, the response of counties to the legislative mandate was to shift hours to times when early voters were relatively uninterested in casting ballots while doing nothing about mid-day congestion.

Early Voting Congestion in North Carolina

The surest sign of congestion is wait times. I’ve worked hard to help states and local jurisdictions match resources to voters, to reduce wait times. What happened in North Carolina in 2014 is an example of what not to do.

The simplest measure of congestion at polling places is wait times. According to answers to the SPAE, North Carolina’s are among the longest in the country when it comes to early voting. In 2014, North Carolina’s average early-voting wait time was 8.5 minutes (+/- 2.9 min.), compared to 4.2 minutes (+/- 0.4 min.) in the rest of the nation. In 2016, North Carolina’s average early voting wait time was 18.9 minutes (+/- 5.1 min.), compared to 12.4 minutes (+/- 1.0 min.) nationwide.

So, while there is no hard evidence that North Carolina’s voters are confused about the times when early voting sites are open, there is evidence that North Carolina’s early voting sites are congested, and more congested than the rest of the nation. One source of this congestion is probably the under-availability of early voting hours in the middle of the day during the week. Forcing counties to offer more early voting hours before 9 and after 5 not only strains county budgets, but it requires counties to exacerbate existing congestion problems.

There is (at least) one important caveat here: The analysis I’ve offered is at the state level. Important decisions about early voting are made at the local level, even when the legislature imposes mandates. That means that the problem of the mismatch between the supply and demand of early voting during the day varies across counties. In some places, the problem will be worse than I describe here, but in other places, it will be better.

Q: Why Don’t Early Voters Vote Before and After Work? A: They Don’t Work on the Day They Vote

One thing seems to have been missed in all this effort to mandate when counties offer early voting in North Carolina: most early voters are not trying to accommodate their work schedules on the day they vote.

In 2014, I was able to do an over-sample of 10 states as a part of the Survey of the Performance of American Elections, one of which was North Carolina. In these states, I interviewed 1,000 registered voters (not the typical 200 in the regular nationwide survey) and asked them about their experience voting. Thus, I had a healthy number of early voters in North Carolina (353) to talk to.

One question I asked was, “Please think back to the day when you voted in the 2014 November election. Select the statement that best applies to how voting fit into your schedule that day.” The response categories included things like “I voted on the way to work or school” and “I voted during a break in my work- or school day.”

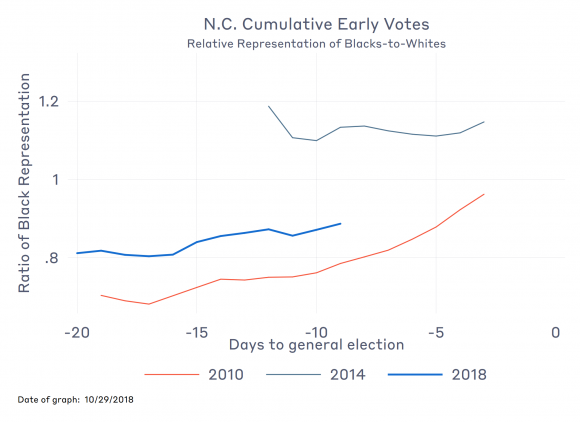

One of the responses categories was “I did not have work or school the day I voted,” which 64% of early voters chose as a response. This compares to 52% of Election-Day voters. A disproportionate number of early voters were retired (32%) or permanently disabled (11%), compared to 23% and 5%, respectively, of Election-Day voters.

It is hard to believe that the expansion of early voting hours will drive retirees and the physically disabled out of the early voting electorate, nor will it bring in more full-time workers, who were not enticed to vote early in 2014.

Conclusion: Legislative Mandates and Local Control

North Carolina has gotten to be known as the place where the legislature is happy to make changes to the state’s election laws and then leave it to the state and county boards of elections to figure out how to implement them. The early voting mandate from this summer fits into this category. While I am the last person to argue that state and local election boards make the right decisions all the time, I think that, on net, the evidence has been that county election boards in North Carolina have been trying to balance fiscal responsibility with demand for early voting within their localities over the past several years. The blanket requirement that counties expand early voting hours to under-utilized times of the day undercuts these local good-faith efforts.

Of course, the evidence also suggests that some county boards have been under-providing hours in the middle of the day. It would be nice if the legislature would turn its attention to that problem. And, it would also be nice if they paid for it, too, but that’s another topic for another day.

Finally, am I predicting an early voting disaster in North Carolina this year? No. Midterm elections are low turnout affairs. Even in this year when political interest is up, North Carolina has no big-ticket items on the statewide ballot. The most likely outcomes to the added congestion and mis-match of supply-and-demand for early voting hours will be minor inconveniences in most places.

The real worry is 2020, when North Carolina will again be a presidential battleground state and the race for governor and U.S. Senate will no doubt be tight, as well. In that environment, the new changes to the early voting law will come home to roost in North Carolina. Can you say, “Florida 2012?”